Captain William Hicks, USN Ret.

Read Part 7

Squadron Commander

My tour on the Nuclear Propulsion Examining Board (NPEB) was extremely satisfying. We had the opportunity to see many crews demonstrate excellence in nuclear operations and administration. We had the opportunity to spread the best practices across the fleet. Based on the comparison from when I was an engineer to becoming the NPEB senior member, the

competence of the fleet had improved dramatically which was fundamentally the result of the expectations for improvement fostered by each generation of NPEB members. One of the lessons that some of the junior members learned, to their regret when they returned to the fleet, usually as a submarine’s Executive Officer, was that the expectations they defined on the NPEB were the

expectations they would have to meet on their own ship. That knowledge held some unreasonable ideas in check.

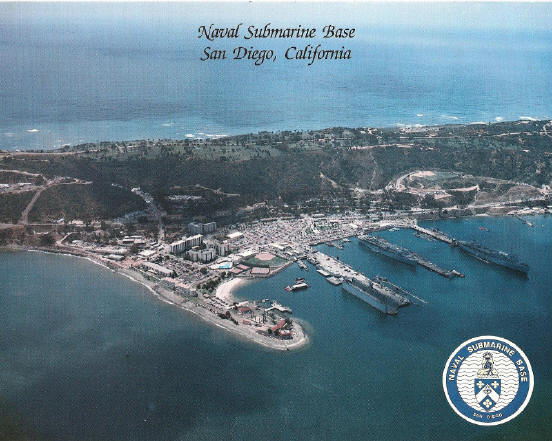

As the end of my second year approached, I was informed that I was to become a Squadron Commander by forming the new Squadron Eleven in San Diego. So, we retraced the actions and the challenges of leaving Norfolk and returning to San Diego. Our house in York County was not sold by the time we had to depart, but it was in the hands of an agent who lived

across the street and there was activity in the housing market so I was confident it would sell, which it did within a couple months. We headed back across country with our camper and a car in tow. Within 100 miles the camper acted up which caused a couple days delay in the repair shop until it was determined the gas line flexible hose had a hole which was causing the

indications of clogged gas filters. That being fixed, we resumed our trek taking a southern route through Nashville, and route I 40 past the Painted Desert, Petrified Forest, Grand Canyon, Albuquerque and Phoenix and into San Diego.

Our housing in San Diego was provided since we would have a house on Submarine Base, San Diego. However, even that was a problem since our house was occupied by the Commander of another squadron and would not be vacated for a month or more after our arrival. In the interim, we had a suite and a room in the Bachelor Officer’s Quarters. The boys were

happy since they had their own room away from us across the hall from the pool table with a patio door onto the beach. We parked the camper and moved into the BOQ.

Unlike in Norfolk, we did not have to move out on weekends. Our household goods went into storage. Mary met her challenge of finding a school for the boys. For the oldest it was not a choice. He went to Point Loma High School. For the fourth grader it was a choice as to which elementary school to apply to since there was no specific, designated school

for the base. That also meant that Mary would be in charge of school transportation since there were no school buses from the base. I got busy reacquainting myself with the commands and activities on the base and setting up the new squadron. Squadron Eleven was to take operational responsibility for the submarines which had been assigned to the Flotilla under the Admiral who

was also responsible for two other squadrons and coordination of the San Diego Area. The decision made at high levels was that there needed to be a squadron staff to oversee the submarines while the Flotilla, or Group as it was officially known, oversaw the activities of the squadrons, the base, and interest of the Pacific Fleet Submarine Force commander.

On a personal level, I knew the current Group Commander was not happy to lose the operational responsibility for the submarines. It was viewed by some as a result of inadequate attention to the individual submarines by the Group staff. From my time on Bates that was part of this Group, I

did not feel a lack of attention or help from the Group Commander of Staff. Throughout the period including the change of command, the Group Commander was extremely helpful and supportive for which I was most appreciative. Starting a new squadron had a unique set of challenges from writing the organizational and operational documentation to deciding on a logo for the

squadron. The staff was pulled together from elements of the Group staff and new additions, so there was a core group who had formed the midlevel managers of the Group staff. This included the squadron engineer and his staff and the squadron weapons officer and his staff and the communicator. The senior staff of the Squadron- the commander, chief of staff, and deputies were

all new. However the old and the new blended together well and we were up and running as a squadron very quickly.

On a personal level, I knew the current Group Commander was not happy to lose the operational responsibility for the submarines. It was viewed by some as a result of inadequate attention to the individual submarines by the Group staff. From my time on Bates that was part of this Group, I

did not feel a lack of attention or help from the Group Commander of Staff. Throughout the period including the change of command, the Group Commander was extremely helpful and supportive for which I was most appreciative. Starting a new squadron had a unique set of challenges from writing the organizational and operational documentation to deciding on a logo for the

squadron. The staff was pulled together from elements of the Group staff and new additions, so there was a core group who had formed the midlevel managers of the Group staff. This included the squadron engineer and his staff and the squadron weapons officer and his staff and the communicator. The senior staff of the Squadron- the commander, chief of staff, and deputies were

all new. However the old and the new blended together well and we were up and running as a squadron very quickly.

The responsibilities of the squadron commander are simply to make the elements of the squadron function effectively and to encourage improvement in all aspects of operations from the repair department on the tender, to the dry dock, to nuclear operations, and tactical proficiency on the individual submarines. The challenge was to know where to focus my

energy and attention and to see the issues before they became problems. The Squadron Commander also had a more visible role in the civilian and broader Navy communities. As with my experience in Squadron Six, some ships required more attention than others since some commanding officers were more mature and experienced than others. One of the significant surprises was how much

direction some commanding officers required up to and including formal letters of instruction. I was not prepared to be as corrective and forceful as I found to be necessary. On the other hand, some of the commanding officers were exceptional and ran a ship that required little attention by the staff to maintain continuing excellence.

Determining which commanding officer was in which group was an early challenge for me and my staff.

It seemed like the challenge for the Squadron always revolved around oversight and assistance of a unit in gaining readiness for some key event. Events such as the start of a deployment, an Operational Reactor Safeguard Examination (ORSE), or a Nuclear Weapons Readiness Inspection.

During the period 1986 to 1989, the Cold War was in full focus and the Soviet submarine threat was at its peak. With benefit of the information gained from the treason of the John Anthony Walker spy ring, the Soviet Submarines were quieter and operated in a manner to make tracking and locating most difficult. In order to enhance our ability to know

where they were, how they operated and to increase our own capabilities, we conducted a lot of deployments for surveillance as well as to detect and track individual units of the Soviet Submarine force.

Deployments came in two flavors. The formal deployments were nominally for six months in the Western Pacific under the operational control of Seventh Fleet with special operations under the direct control of COMSUBPAC. Mini-deployments directly from San Diego and returning to San Diego were usually 59 days and did not officially count as deployments to

comply with a number of rules associated with operational tempo. However from the point of view of the ship and the Squadron, whether it was a six-month deployment to WestPac or a 59 day port to port ASW deployment, the preparations and the definition of readiness were essentially the same.

Readiness was defined by minimal material deficiency, fully stocked repair parts, consumables, and food, and operational and tactical proficiency. Tactical proficiency was monitored through a session in the attack trainer at the submarine training facility on the base as well as during operations at sea. In preparation for deployment, we always

developed a focused week of exercises which included the types of scenarios the ship might encounter. This included tracking exercises as well as exercise weapons firing. The Squadron responsibility was to develop the operational orders, provide the exercise participants, ensure proper submerged separations, provide observers to ride the ship during the exercise week, and

manage all aspects of the exercise weapons events.

During my three years at the Squadron, we refined and improved the various elements of the pre-deployment exercises that enhanced the challenges for the crews and improved their ability to fight their ship. One of the most challenging exercises involved both submarines being able to actually fire exercise torpedoes. The safety controls for this event

were particularly critical since it would develop that there were two submarines and two torpedoes within the same area of water, protected from physical interactions only by depth limitations. When we could get the correct mix of submarines for an exercise it worked and it significantly enhanced both the tactical skill level and the awareness of the decision challenges to

actually fire a torpedo at what might or might not be an actual target.

As in Squadron Six, either I or one of the deputies spent time in preparations for each ORSE. Again, some commanding officers required more help than others and we planned our time to respond accordingly. We also worked with the tender’s commanding officer and his wardroom to prepare for Radiological Controls Proficiency Examination (RCPE), nuclear

weapons, and propulsion plant inspections.

The following anecdotes reflect some of the more challenging or unusual experiences during my three years as squadron commander:

The movie Top Gun had provided significant recruiting benefit for Naval Air and the submarine force was looking for a similar opportunity to showcase itself. Hunt for Red October became that vehicle. The filming of Hunt of Red October was focused in San Diego and used the ships of Squadron Eleven in the movie. The dry dock scene was filmed in the

Squadron Eleven Dry dock, ARCO.

The submarine emergency surface scene was accomplished by USS Houston.

Most other scenes were conducted in a studio set. During the filming of the dry dock scene, Alec Baldwin was on the pier and many of us went to watch. The setup to film the scene was impressive. The movie also provided opportunities for officers and sailors to act as extras and in at least one case a lieutenant from one of the Squadron submarines had a

speaking part as a naval officer controlling an attack. I guess it was easier to train the officer to be an actor than train an actor to be an officer. We also provided a day at sea for the cast on a 688-class submarine to see how things really happened at sea. Unfortunately Sean Connery did not make the trip, but most of the other key actors and directors for the film were

aboard. It was a different and interesting change from our normal routine.

We were to get a new submarine into the squadron who was coming from an East Coast Squadron via a deployment to Westpac. The submarine was due for an ORSE shortly after arriving in San Diego so I determined it advisable to take a good look at it prior to return from deployment. I arranged to meet the ship in South Korea and ride to Guam and then Japan

and fly home from Japan. Quite a travel adventure: when I arrived in Seoul, South Korea, I had to move from the international to the domestic terminals. Unfortunately, there had been a recent terrorist attack in Korea and they were on high alert. The number of guns and troops that were in and around the airport and the way they scanned all the passengers—particularly the

foreigners was scary. Once I arrived in the domestic terminal, I caught a flight to the south where I was met by a car and driver who took me through some rugged country to a South Korean Naval Base (the name escapes me) where the ship was docked. My quarters were a three bedroom guest house in which I was the only occupant. I met the ship CO whom I had known from previous

encounters when I was on the NPEB and when he was on the COMSUBPAC Staff when I was CO of Bates.

We got underway the next day and had a beneficial transit during which I had the opportunity to observe many drills and operational demonstrations. It was clear the crew was rusty due to the intense special operations which they had just completed, but they showed significant improvement while I was aboard and I was confident they would do fine on the

ORSE which is how it worked out. It was also apparent that my presence invigorated the interest in more intense training during the transit; a beneficial trip.

While the tender is normally in port supporting the squadron submarines, there were opportunities and requirements for it to leave port. Periodically, the tender must go to sea to empty the tanks filled with radiological effluent that they had collected from the submarines alongside. This was normally a couple days at a time with minimum impact on the

upkeep schedule for the squadron submarines. Other at sea taskings were longer and more disruptive to the submarine upkeep schedules. In one case, the tender went to sea and anchored in relatively shallow water to demonstrate its ability to provide support to an SSBN at sea. In another situation, the tender was tasked with transit to Seward Alaska to provide support to the

USS Alaska, SSBN 732 as it made a visit to its namesake state. During the return transit to San Diego, the tender stopped in Seattle for a visit. On the transit out of Seattle, a sailor gave birth in the berthing compartment. No one acknowledged they knew she was pregnant. During the transit to and from Alaska, everyone wore heavy clothing - the apparent reason her condition

was not obvious. The mother and baby were removed from the ship near Seattle and the trip to San Diego resumed. For that tender, the term berthing (birthing) compartment took on a new meaning.

The tour as a Squadron commander is normally a two-year assignment. As the two-year point approached, I was told I was going to Washington for my first shore tour since my Nuclear Power School staff assignment in Mare Island. My relief was identified and Mary and I took a trip to look for a house. Not so fast: still an apparent slow learner, I was told

after our house hunting trip that the orders for my relief were cancelled and that there was no one else to relieve me - so I was to stay for another year. That was good news for a couple of reasons: Our oldest son was getting ready to enter his senior year in high school and it would have been a significant sacrifice for him to miss his senior year in the school where he was

established. Also, since my tour in Washington was not one from which I could expect to be selected for Flag Officer, I was in no hurry to get started. Finally, Squadron commander was a pretty good position in which I was comfortable and from which I felt I was doing some overall good for the Submarine Force and the Navy.

Shore Duty At Last- Beware What You Ask For

So, the transfer was on hold and I spent an additional year at Submarine Base San Diego. Now that our oldest was to complete high school in San Diego and my next assignment was not clear, the choice of a college became interesting. Should he apply on the West Coast or the East Coast? To cover all bases, he did both and he was accepted on both coasts.

When my third year was coming to an end, I was given a choice of several senior Captain billets in either Pearl Harbor or Washington none of which were particularly appealing. Since it was bad form to retire from the position of Squadron Commander, I decided to delay retirement for one more tour but to pick the one that seemed the most convenient for my family. As a result, I

agreed to my first tour in the Pentagon as a senior Captain. What a learning experience that was not always fun and not always successful. I got orders to the staff of the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) for Logistics, OP 04. This assignment opened a whole new area of challenge. But first we needed to get from here to there.

With no house to sell in San Diego, one of the major headaches of transfer was removed. Having had time for house hunting trips to the Washington area allowed us to buy a house before arrival removed an additional stress. We decided that the camper was no longer the conveyance of choice across country since we had two cars and our oldest could drive

one with his brother that they thought was a wonderful idea; no one to criticize their music choices. We sold the camper in San Diego and made the plans to drive cross-country. On the day before we left it became apparent that one car had a problem that we could not trust on the trip so the evening before departure I was in Mission Valley to buy a new car.

With the boys in the new car, we headed out of San Diego. We had two-way radios in each car to keep in contact and keep the boys on track. Our small convoy stayed relatively close together and the trip was mostly uneventful. After visits to family on the trip, we arrived in Burke Virginia to start my last tour in an entirely new environment. Our

youngest entered the local high school as a freshman and the oldest made a choice of the five colleges he had been accepted. He chose to attend Penn State to which he moved soon after our arrival.

With the family details on track, I looked towards the new challenge. Rather than being the squadron commander with a car and driver on call and a staff to carry out my agenda, I now rode the bus and was a worker on the staff of two admirals with a shared secretary and no staff. I even had to learn how to use a computer for email.

I had decided at the squadron that I could see no advantage to email since hand written notes served very well. I had noticed that the younger guys on the ships had computers and that some networking was occurring for things like work orders and supply requests. I also remembered the attempts while I was at Squadron Six to use bar code technology to

maintain inventory control on the tender. Also, both my boys were very computer literate doing programming and games on an Apple IIC which I had bought, but never learned how to use due to lack of interest. For me, the computer revolution had not yet occurred, but the time had come.

When I reported to OP 04 in the Pentagon, I learned that I was to be the Navy point person for CALS (Computer Aided Acquisition and Logistics Support). In 1989 when I reported to Op 04, the internet was embryonic and the World Wide Web had not been developed. The connectivity was limited to copper telephone wires so data transfer was very slow.

Computers were just being introduced to tasks such as design, manufacture, and digital data management. Computer processing speeds and memory capacity were slow and small. However, in that environment the Deputy Secretary of Defense, William Taft IV directed that the services aggressively pursue computerization of the acquisition and logistic processes across the Department

of Defense. From this direction came the mandate to the services to expedite the introduction of CALS to all functions. Each service headquarters logistics organization was mandated to identify a central point person responsible for integrating the new digital technology into the logistics practices.

I was that person working directly under the three star Admiral OP 04 and his two star deputy. The other services had created similar offices within their logistics organizations, all of which were headed by Four Star Generals. It was an initiative with very senior interest across the services since it had been mandated by the Deputy Secretary of

Defense. Talk about a steep learning curve.

The CALS initiative was led in DOD by a senior civilian with whom we worked closely to coordinate activities and efforts. My experience in the fleet introduced me to many of the challenges that CALS had the promise to fix: Piping and components that did not align due to small differences on joining plans or small manufacturing deviations; technical

manuals that were out of date due to cost and time to keep them updated; tons of technical documentation aboard ship which took up vital space and weight; spare parts that were not available or could not be located; maintenance procedures that were not current; training courses that were not current; maintenance efforts that were unsuccessful due to differences in the precise

location and layout of shipboard spaces; and many more.

What I had to learn was how CALS would mitigate these challenges. Looking back today, the answer is clear. In 1989 it was not so clear. Even more challenging, it was not clear to the organizations that would have to implement the changes. Probably more challenging was that standards did not exist to ensure commonality and interoperability of the parts

of the initiative. Basics like how to create an electronic book (think Kindle) had not been developed and agreed upon. Just in time digital printing capability was a concept but not a reality. Computer Aided Design/Computer Aided Manufacturing (CAD/CAM) was being developed, but without consensus standards so that the digital data format for one system would be compatible with

other systems.

The lack of a high speed digital data transfer capability or large capacity digital storage processes was a challenge to be overcome. There were many lessons to be learned: Just because you come from OPNAV does not mean anyone will listen, nor do you necessary have the authority to force them to listen or act; many vendors and computer related

manufactures wanted to get in on the action and assumed I had money to commit which meant I had a lot of "new friends"; the development of the standards and processes to make CALS a reality required real research and demonstration which required money; convincing those with the money to share some for CALS development was a challenge; the best source of development expertise

resided in industry who wanted to participate, were reluctant to share what they knew openly, were reluctant to provide research efforts from their own budgets, but wanted to be players.

It was determined that the best way to get CALS going was to convince the services to require CALS in acquisitions. The first step was to require/cajole/encourage demonstration acquisitions. At least one Weapons system from each service such as the Seawolf Submarine, M1A1 Abrams Tank, A12 airplane, and next generation fighter plane (F35) were

designated as CALS demonstration projects and the procurements required digital design, manufacture, and technical documentation to the extent possible. In order to get these commitments, there were lots of interactions with very senior services logistics managers which was an environment into which I was totally na•ve but a fast learner.

After about a year as the Navy point on CALS, the senior logistics managers were convinced to form a Joint CALS Management Office to more effectively integrate and facilitate the maturation of CALS across all services. I was designated to form and head the office. JCMO was the acronym. Each service assigned one or more officers or senior civilians to

the office. Our budget was what we could beg from each service. Our effectiveness was not what I had hoped since the individuals assigned by the individual services never lost their allegiance or connection to their service and were not willing to look to advance CALS if it did not also immediately benefit their service. However even with the limitations we made progress in

maturation of the demonstration projects, advancement of the initiatives to develop digital technical standards, and conduct a mapping of the origin and uses of technical data across weapons projects.

A final challenge was that as CALS got visibility and some stature, it became a target for upwardly mobile civilians in DOD who for their own reasons undercut and usurped some of our initiatives. It was time to retire which I did in September 1991. Shortly after my retirement, JCMO was absorbed into a DOD office and most of the service assignees

returned to their service. Looking back in light of the fiber optic infrastructure development with the "dotcom" boom and the amazing advancements in computational speeds and digital storage capabilities, many of the issues we faced are humorous. However, I believe that CALS was a vision that jumpstarted a number of initiatives and capabilities that have been instrumental in

achieving the benefits from the computer and digital technology in general.

During this tour, the Gulf War I occurred when Iraq was expelled from Kuwait. I was only an observer, learning more from the evening news than at my job. It was not the type assignment that took advantage of the talents I had developed during the previous 28 years, but I guess someone had to do CALS and I was chosen. The Submarine Force had no more use

for my capabilities.

Retirement - Consulting and Department of Energy

Following my retirement, I did some consulting which looked to my CALS knowledge and access but that was short-lived. I had been approached just prior to retirement by a senior naval officer who was assigned to the Department Of Energy looking for retiring, nuclear trained officers to join DOE to enhance the process improvements that the Secretary of

Energy, Admiral James Watkins was implementing. When I indicated interest, I was interviewed and quickly hired in support of the initiatives to improve the formality of operations within the nuclear operations under DOE responsibility. I continued in that role for the next 20 years. Many of the lessons I learned back in the shipyard in Quincy Mass are still relevant and still

a work in progress at DOE. Once I retired, I stayed in the house in Burke for the next 20 years. Mary had moved enough times following my Navy career and was not interested in more moves in a post retirement career. I agreed.

Read part 9

Read other articles by Captain William Hicks