Khodahafez

Scott Zuke

(10/2013) "Have a nice day!" "Thank you. Khodahafez." This, according to a Twitter account belonging to Iran's President Hassan Rouhani, is how the first direct talks betwen U.S. and Iranian leaders since 1979 concluded on September 27. President Obama ended the 15-minute phone with

the Persian equivalent of 'goodbye,' which translates as "God go with you."

(10/2013) "Have a nice day!" "Thank you. Khodahafez." This, according to a Twitter account belonging to Iran's President Hassan Rouhani, is how the first direct talks betwen U.S. and Iranian leaders since 1979 concluded on September 27. President Obama ended the 15-minute phone with

the Persian equivalent of 'goodbye,' which translates as "God go with you."

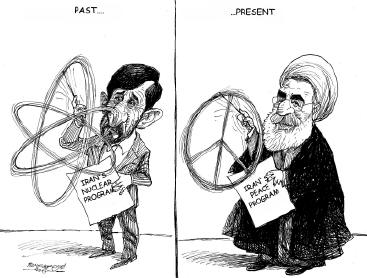

Since Rouhani stepped in for former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in August, a stunning transformation has occured in Iran's diplomatic stance toward the West--one that is moving so quickly that Iran itself can't seem to keep up. It is a widely-noted irony that Rouhani's Twitter account has become such an important tool of his diplomacy when, for now

at least, Iran's citizens are still denied access to Twitter and other social media sites.

In a year marked by overwhelming violence in the Middle East and tinged with a melancholy acceptance of the world's political impotence to resolve the region's numerous crises, the sudden softening of tensions with Iran seems too good to be true. To many Israelis, it's even downright suspicious. It was just over a year ago that the two nations appeared

to be on the verge of an armed confrontation over Iran's nuclear program, and now Israel's leaders are warning that Rouhani's gestures are only a tactic to divert attention away from what they believe to be Iran's goal: joining the fraternity of nuclear-armed nations.

That remains to be seen, and it's natural to say that words are not enough--that Iran must make real, tangible actions to back up its friendlier tone (and tweets). But in what has essentially been a three decade-long war of words, a change in rhetoric is significant in and of itself.

It's worth remembering that Israel and Iran have not historically been enemies, nor have they engaged in open hostilities. The idea that Iran could pose an existential threat to Israel has been based almost solely on rhetoric since the 1979 revolution, especially Ahmadinejad's firey and provocative statements over the past decade. But despite all of

that, the conflict between the two countries is not marked by the scars of violence and terrorism like other disputes in the region. "In the back of the historical memory of the Israelis, when you speak about Iran, Iran is considered to be a good friend of Israel," said David Menashri, an Israeli expert, in an 2012 CNN article.

While Iran's political trajectory is still ultimately decided by the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, it shouldn't be taken for granted that Rouhani, known to be a moderate very different from Ahmadinejad, was elected with strong support from the Iranian people. This sends a signal to Khamenei as well as the rest of the world, that Iran is under

internal pressure to take its diplomatic strategy in a different direction. Yes, Iran will insist on the right to develop its own advanced technologies, especially nuclear energy, and Khamenei will never let go of the Islamic revolution that first put Iran at odds with Israel and the West. But he may come around to the idea that the global community is willing to cooperate

with an Islamic Iran, and that such an arrangement would be preferable to isolation and harsh sanctions that have seriously harmed Iran's economy.

The reason that shift of position may just be possible now is due in part to President Obama's Middle East strategy, which has been characterized as "measured and cautious" by supporters, and "leading from behind" by detractors. Either way, it's been a consistent show of restraint compared to predecessors, and as a result, Iran has every reason to feel

more secure against the threat of outsider influence and threat of regime change these days. Even the world's current number one pariah, Syria's Bashar al-Assad, has managed to stave off international intervention in his three-year-long civil war. At the same time, the region has seen home-grown revolutions in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia come to the brink of devolving into

civil wars of their own. No rational policymaker would be pushing for a major revolution in Iran right now.

Khamenei's belief that the West and Iran are ideological and mortal enemies, and that the U.S. is always secretly working to engineer a revolution could be characterized as paranoia, were it not for the CIA's recent admission of its role in Iran's 1953 coup that overthrew the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. Exchaning

pleasantries is one thing, but restoring diplomatic trust with such a history will be a long process.

The potential benefits of investing in an improved relationship are certainly worthwhile, though. Driven to isolation, and labeled by former President Bush as a member of the "Axis of Evil," Iran was forced into a positon where it had to pretend to be crazy enough to build--and use--a nuclear weapon. Under Ahmadinejad's strategy, this was seen as the

only way to be treated respectfully by the international community, but it put the whole region, and the world, on edge. It also pushed Iran toward building a closer alliance with Russia and China, who have been working to consolidate a coalition with the power to work outside of the rules imposed by the U.S. through global institutions like the UN.

Iran's sudden turn will not immediately satisfy Israel, nor will it sufficiently alter the political landscape to find a meaningful resolution in Syria, but there's nothing to lose by welcoming the friendly gesture and showing that the door really is open for it to rejoin the international community. The West will have to be prepared to take concrete

actions to show good faith as well, though, because just as we have skeptics here, Iran has its own influential players who believe the U.S. will stop at nothing to keep them isolated and vulnerable.

"I don't believe this difficult history can be overcome overnight ," President Obama told the United Nations. "The suspicion runs too deep." But a phone call and some tweets are a good start.

Read other article by Scott Zuke