Nothing to Stand On

Scott Zuke

(5/2014) In the United States, most people would probably agree that media coverage of elections overwhelmingly focuses on day-to-day horserace politics, setting aside relatively little time to discuss the substance of candidates' platforms. If you're not sure that's true, just think of

the knee-jerk headlines about the potential impact of Chelsea Clinton's pregnancy on her mother Hillary's prospects for winning the presidency in 2016. Clinton, of course, isn't even a declared candidate yet, so we're a ways off from having any platform to evaluate, but even when all the hats are in the ring, the attention will mainly be on campaign tactics rather than the

issues forming the candidates' visions for the country's future.

(5/2014) In the United States, most people would probably agree that media coverage of elections overwhelmingly focuses on day-to-day horserace politics, setting aside relatively little time to discuss the substance of candidates' platforms. If you're not sure that's true, just think of

the knee-jerk headlines about the potential impact of Chelsea Clinton's pregnancy on her mother Hillary's prospects for winning the presidency in 2016. Clinton, of course, isn't even a declared candidate yet, so we're a ways off from having any platform to evaluate, but even when all the hats are in the ring, the attention will mainly be on campaign tactics rather than the

issues forming the candidates' visions for the country's future.

The United States can function this way because it is secure, stable, and has a relatively tidy balance between two parties that are bigger than any individual candidate. That is, most voters can make a simple decision based on the historical platforms of the Democrat and Republican parties, without having to care that much about the person who is

actually running for office. But what if this balance didn't exist?

The Middle East has had a flurry of elections recently, spanning from Algeria to Afghanistan. Some have been in the form of popular votes, like we are used to, while others have been parliamentary procedures to form new governments. What is similar across the board is that most candidates in these races don't really have policy platforms.

In Egypt, the frontrunner for president, Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, has coyly withheld any specific details of his electoral platform, with some experts speculating he will not discuss it until he has already won.

Algeria's 77-year-old president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, who can barely talk or move after a suffering a stroke last year, easily won re-election in April despite hardly running a campaign and rarely appearing in public. This wasn't due either to his popularity or even to vote rigging, but to the fact that the country doesn't have an established

succession mechanism, and the main political factions haven't had time to line up viable alternatives.

Afghanistan's presidential election last month managed to attract the same voter turnout as the last U.S. election (58%), an incredible accomplishment considering the Taliban had threatened terrorist attacks on polling stations. Here too, though, there's not really such thing as political platforms. Rather, citizens vote according to their ethnic

identity.

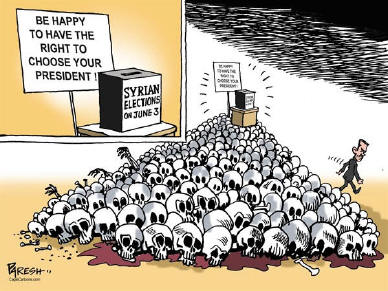

In the midst of a civil war that has killed as many as 150,000 people and displaced millions, Syria's Bashar Al Assad recently announced a presidential election set for this June. An editorial by ‘The National’, asked: "On what platform does Mr Al Assad intend to stand? Stability? Law and order? Peace and prosperity? His regime has done more to destroy

these things in Syria than any foreign enemy has ever managed." More likely his platform will continue to be "opposing extremists," which is as good as saying, "No Hope, No Change."

Other states, like Yemen and Libya, are so weak and fractured that political platforms are an unaffordable luxury. Instead there are caretaker transitional governments just struggling to hold things together and maintain some semblance of legitimacy. Both are attempting "national dialogues," an ongoing series of meetings and conferences aimed to bring

people together to discuss a framework for future governance and contribute to the drafting of a new constitution.

Iraq, which held parliamentary elections on April 30, is on the surface more unified under Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, although analysts are warning that without a change of leadership or policy to become more inclusive, a political fracturing may be imminent. Violence has been spiraling out of control for months, and sectarian tension is on the

rise. As a result, says the Economist Intelligence Unit, campaigning has become mostly about sectarian affiliation, and policymaking has become ineffective.

The absence of campaign and political platforms throughout the Middle East paints a picture of a region just trying to hold itself together at the seams. Visionary leadership is sorely lacking, and those leaders who have been able to secure the tightest control have not been able to convert stability into growth or development.

Sisi, Egypt's presumptive next president, may receive a hero's welcome for his role in deposing Mohammed Morsi and preventing the Muslim Brotherhood from taking the country down a bad path, but without a stated vision for the next few years, there's little hope for accountability. You can't blame a leader for breaking campaign promises if he never

makes any.

One exceptional case in the region has been Iran, where President Hassan Rouhani ran on a clear platform of improving relations with the West as a means to end crippling economic sanctions. Though it's still unclear how successful that strategy will be, the fact that he had a platform gave the Iranian people something meaningful to vote for. They

voiced their will for the policy they wished their country to pursue, and now they will be able to observe it in action and determine whether they are happy with the result.

A vote for Sisi, on the other hand, is only a negative statement: that voters don't want to go the direction the Muslim Brotherhood was taking them. The positive side-the policies the country will pursue now instead-will be determined privately by Sisi.

He may end up leading well. For example, the president of Burma, Thein Sein, was put in power without any specific policy mandate, and he chose to pursue an aggressive process of political and democratic opening, unilaterally moving to end decades of oppression and isolation. Egypt's citizens would be incredibly fortunate to get a surprise like this

from Sisi, although it would be better still for them to be allowed to choose that path for themselves, and then decide who is best suited to carry it out. In democracy, 'what you see is what you get' is far preferable to pleasant surprises.

Read other article by Scott Zuke